|

| |

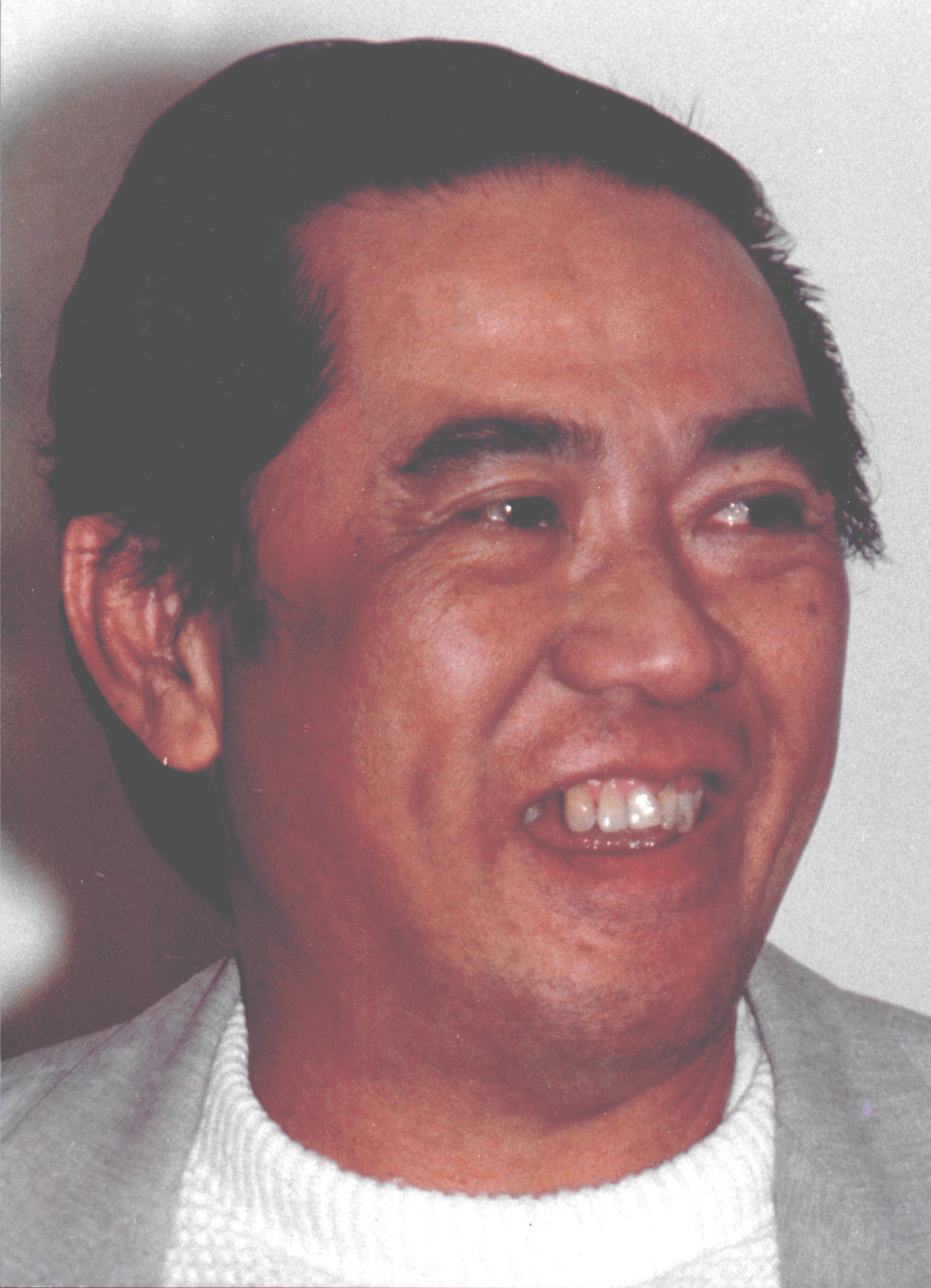

Alfredo Cruz

Alfredo Cruz, a handsome, 56-year old grandfather with a full head of jet-black hair crowning his proud Asian face was traveling with his niece,

Edith to attend his mother's funeral in the Philippines. An accountant by trade, he was in many ways a man of detail and precision, a meticulous

dresser who for some reason chose that day to wear a white Gloria Vanderbilt shirt he had bought the week before for his daughter Exie.

This was “Tay” as we called him (Dad) in Tagalog.

Exie had begged him not to go. Three months before, she had had a

premonition of her father’s disappearance. Later she would call it a vision.

At the time, though, she had no name for it. She had never had a vision before.

While trying to take a nap in her parents’ bedroom, she saw a beautiful wreath of flowers being delivered to her parents’ living room.

She was not sleeping; her eyes were open. Yet, addressing the bedroom wall, she saw the living room.

She saw the sun pouring through her parents’ living room window and falling upon the great wreath of funeral flowers.

Otherwise, the room was empty—there was no casket; there was no body. Exie had begged him not to go. Three months before, she had had a

premonition of her father’s disappearance. Later she would call it a vision.

At the time, though, she had no name for it. She had never had a vision before.

While trying to take a nap in her parents’ bedroom, she saw a beautiful wreath of flowers being delivered to her parents’ living room.

She was not sleeping; her eyes were open. Yet, addressing the bedroom wall, she saw the living room.

She saw the sun pouring through her parents’ living room window and falling upon the great wreath of funeral flowers.

Otherwise, the room was empty—there was no casket; there was no body.

“Who are the flowers for?” she asked.

The answer she received—inaudibly, but nonetheless distinctly—was, “For your father.”

The vision passed.

And almost as soon as the vision passed, Exie dismissed it. At the time, it seemed meaningless.

And by the time of her father’s departure three months later, the vision was almost entirely forgotten.

Exie’s worries now, as she begged him not to go, were much more purely natural.

This was to be Tay’s first trip back to the Philippines since his emigration to the United States 12 years earlier.

Then, Tay had wept, leaving his mother behind. Now he was returning to bury her.

He had a weak heart; now his heart was broken, and Exie worried that the trauma of the funeral, compounded by the stress of overseas travel, might finally break his health.

She telephoned him the night of his departure and tried to talk him out of going.

He dismissed her every plea with a joke, and then at last, after Exie telephoned him a second time, he confided to her why he felt he had to go.

“It’s the last chance I’ll have,” he said, “to serve my mother.”

This was something against which Exie felt she could not argue.

She too had been there 12 years earlier, in the terminal of the Manila airport, amid the bewildering clamor of bodies and voices and noises, speechlessly watching a trail of tears disturb her father’s proud face.

She was 20 years old then, a business school graduate, but she was in many ways still a young girl, still entirely Filipino, and the prospect of casting herself to the fabled and utterly alien shores of America plunged her heart into a whirlpool of conflicting emotions.

But more than any of these vivid daydreams and private anxieties, the sight of her father silently weeping indelibly branded her memory.

Her mother and her youngest sister had been in New York three years already.

Tay had lagged in order to secure a more permanent Visa, and to allow Exie to complete her education.

Perhaps these years together in Manila galvanized the bond between them. In any case, out of the complex and sometimes riotous relationships of a large Catholic family, Exie and her father discovered a quiet, but ironclad, affinity for each other.

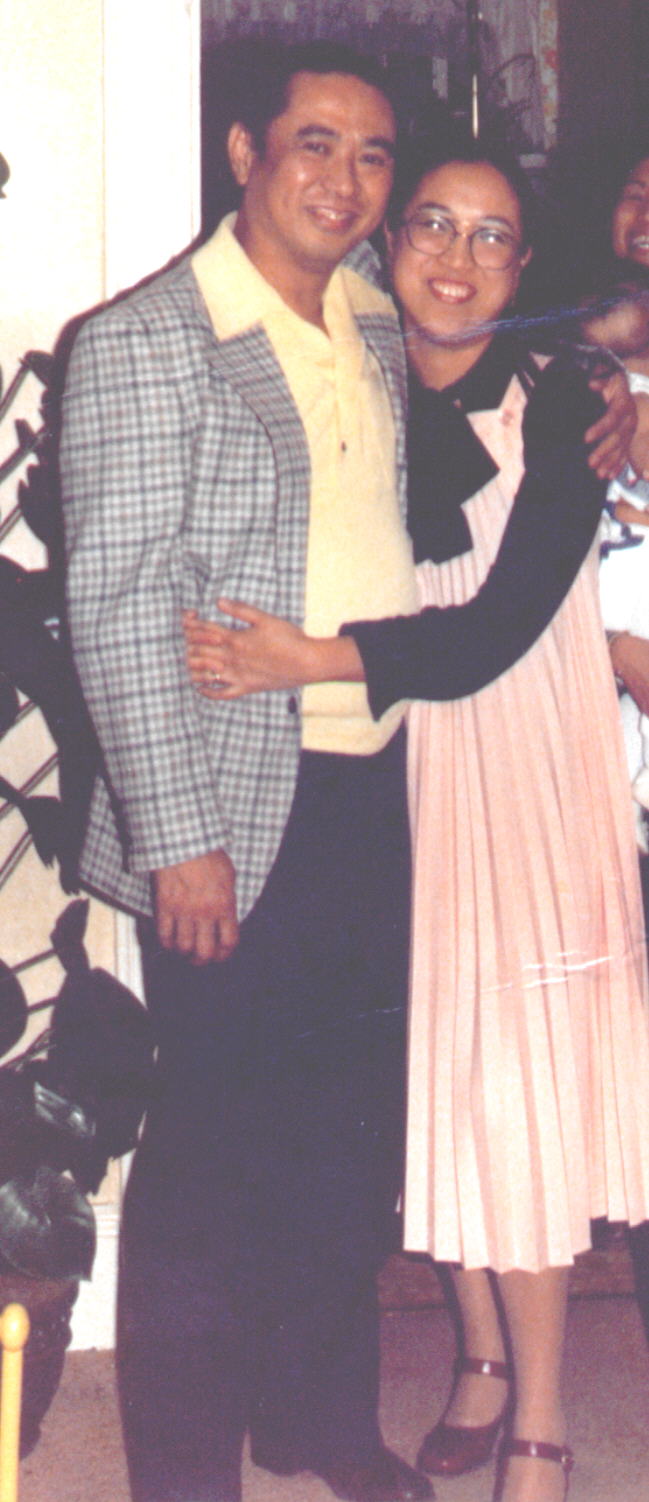

Evidently Tay had shared a similar bond with his mother. And even I, who three years later married Exie in New York, immediately perceived the bond between them.

Jewish, divorced, non-Roman Catholic, non-Filipino and 13 years Exie’s senior, I should have irritated Tay’s every prejudice and jealousy.

Perhaps I did. But if I did, he masterfully concealed his misgivings.

More than that, he received me into his family with warmth, and thereafter treated me with gentle kindness and boundless generosity.

He was not an outgoing man; he was quiet with his family, and in larger social gatherings he clung, according to Filipino custom, to the segregated circle of adult men.

But apart from the society of adults, he loved to play with his grandchildren.

He was an accomplished gardener. And even I, a man on whom subtle signals are sometimes lost, could sense the quiet sympathy that joined him to his daughter Exie.

Exie would later say that in her, Tay discovered someone in whom he could confide, and in her father, Exie had someone who could be trusted to read her silent thoughts, and who knew better than anyone else how to comfort and encourage her.

Doubtless this was so, but this does not begin to describe what I observed.

What I remember best is this: on Sunday afternoons in New Rochelle, as Exie worked about her parents’ house, she would quietly begin to sing songs from her youth.

From another room, her father, who himself had a gifted voice, would join her with a merry whistle, harmonic and true.

The old house would fill with the music of two hearts caroling like songbirds.

It was at such moments that I felt not only that I was seeing the true affinity between father and daughter, but that I was glimpsing the bared soul of my circumspect father-in-law, dancing.

Bert Schlossberg, from Rescue 007: The Untold Story of KAL 007 and Its

Survivors

|